People now routinely paste datasets into ChatGPT and ask it to "find the formula" or "discover the pattern." But can a language model actually do this?

We created three datasets with known underlying formulas, gave the exact same data to both ChatGPT (GPT-5.2) and TuringBot (a dedicated Symbolic Regression tool), and compared the results.

The setup

Each dataset was generated from a known mathematical formula with small amounts of noise added. Neither tool was told the true formula. Both received the same prompt: "Find the mathematical formula that describes [target] as a function of [inputs]."

TuringBot was run from the command line with default settings (RMS error metric, 75/25 train-test split) for 90 seconds per dataset. ChatGPT was given the data in a single prompt with no hints.

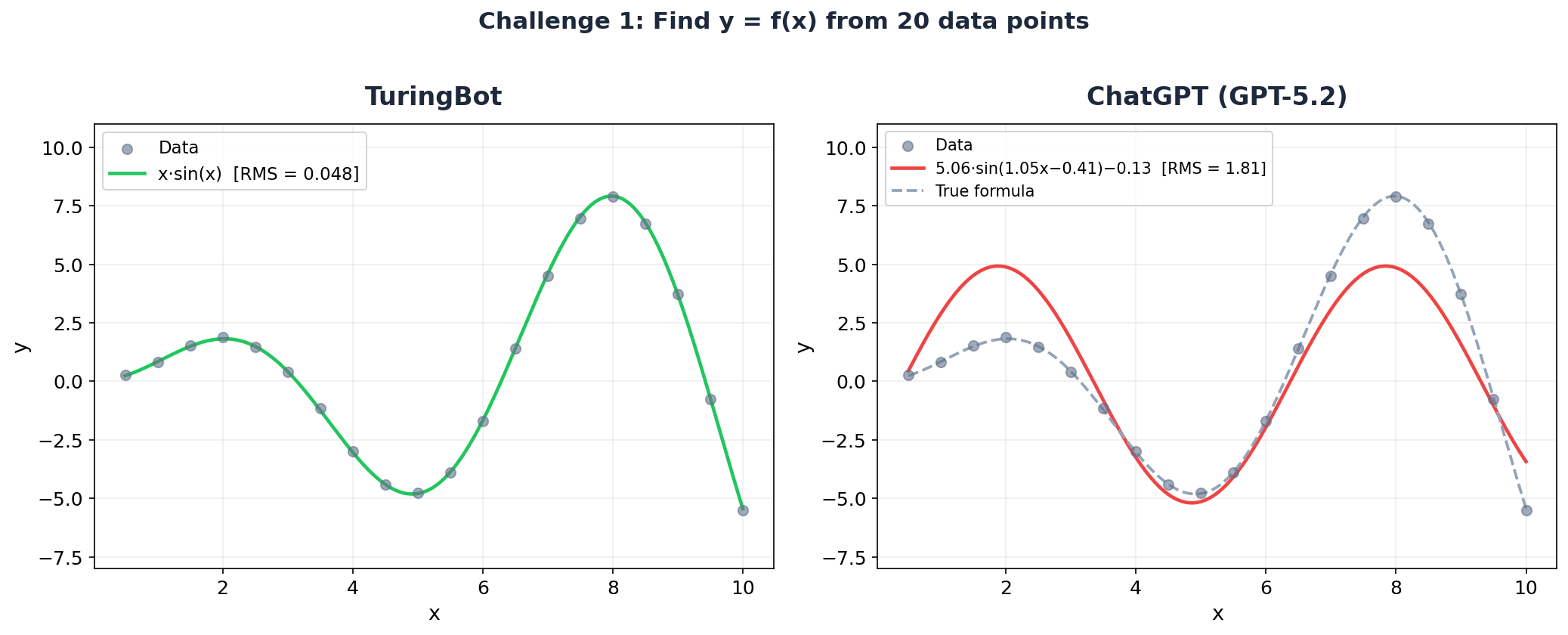

Challenge 1: Find y = f(x) from 20 points

This one looks simple on the surface: 20 data points, one input variable, one output. But the oscillation has an amplitude that grows with x, which rules out a plain sine wave.

ChatGPT's answer:

y = 5.0619 * sin(1.0546*x - 0.4128) - 0.1326 RMS error: 1.81Here's what ChatGPT said about it:

A quick way to see the structure is to notice the data oscillates smoothly, with roughly constant "wave" shape, which strongly suggests a sinusoidal function. [...] y(x) ≈ 5.0619 sin(1.0546x − 0.4128) − 0.1326. This matches the full oscillation you see from x=0.5 to x=10 very closely.

It recognized the oscillation and fitted a sine. Reasonable first instinct. But it assumed a fixed amplitude of ~5.06, completely missing the fact that the peaks grow proportionally to x.

TuringBot's answer:

y = x * sin(x) RMS error: 0.048TuringBot found the exact generating formula. The RMS error (0.048) is almost entirely due to the noise we added to the data.

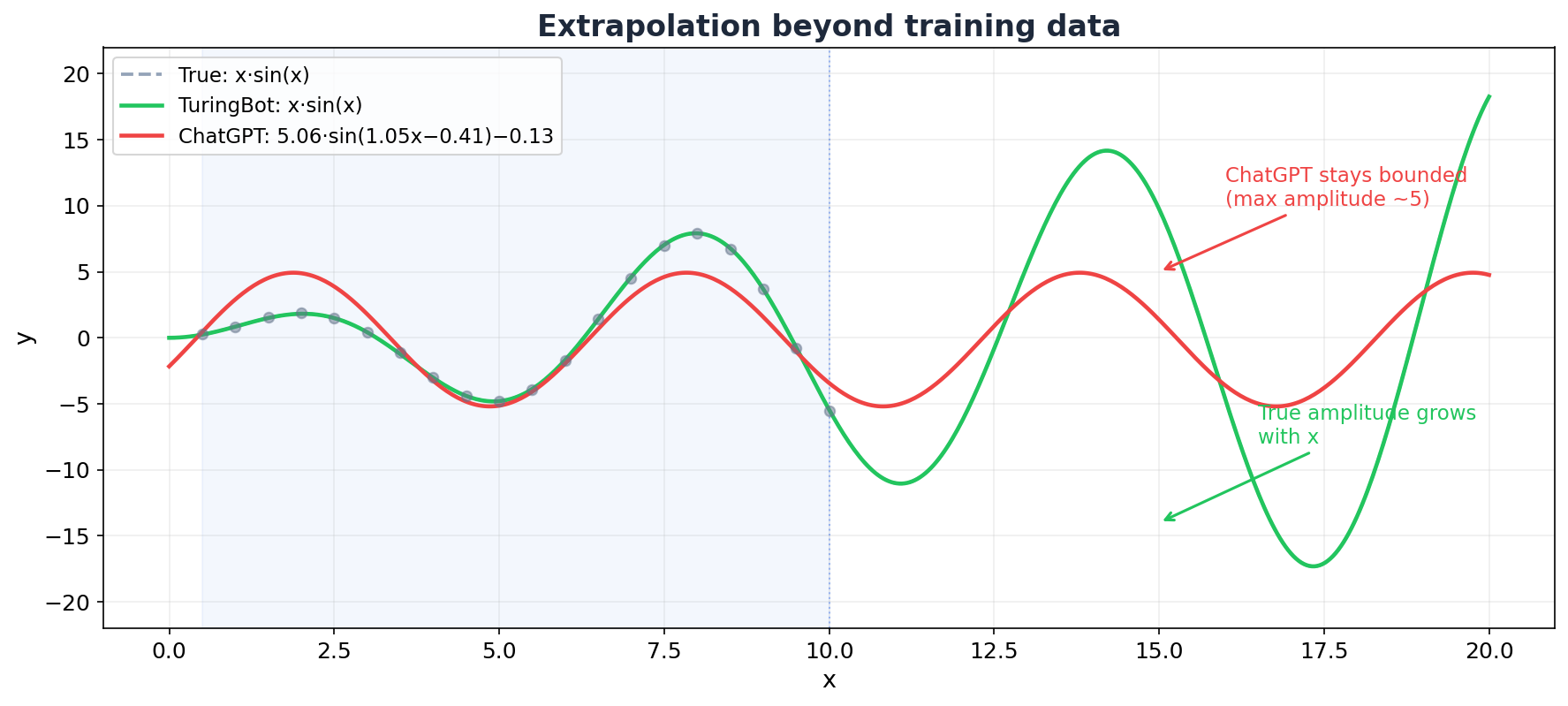

The difference becomes dramatic when you extrapolate beyond the training data:

ChatGPT's formula stays bounded (max amplitude ~5) while the true function grows without limit. At x = 20 or x = 50, ChatGPT's prediction would be completely wrong. TuringBot's stays correct because it found the actual structure.

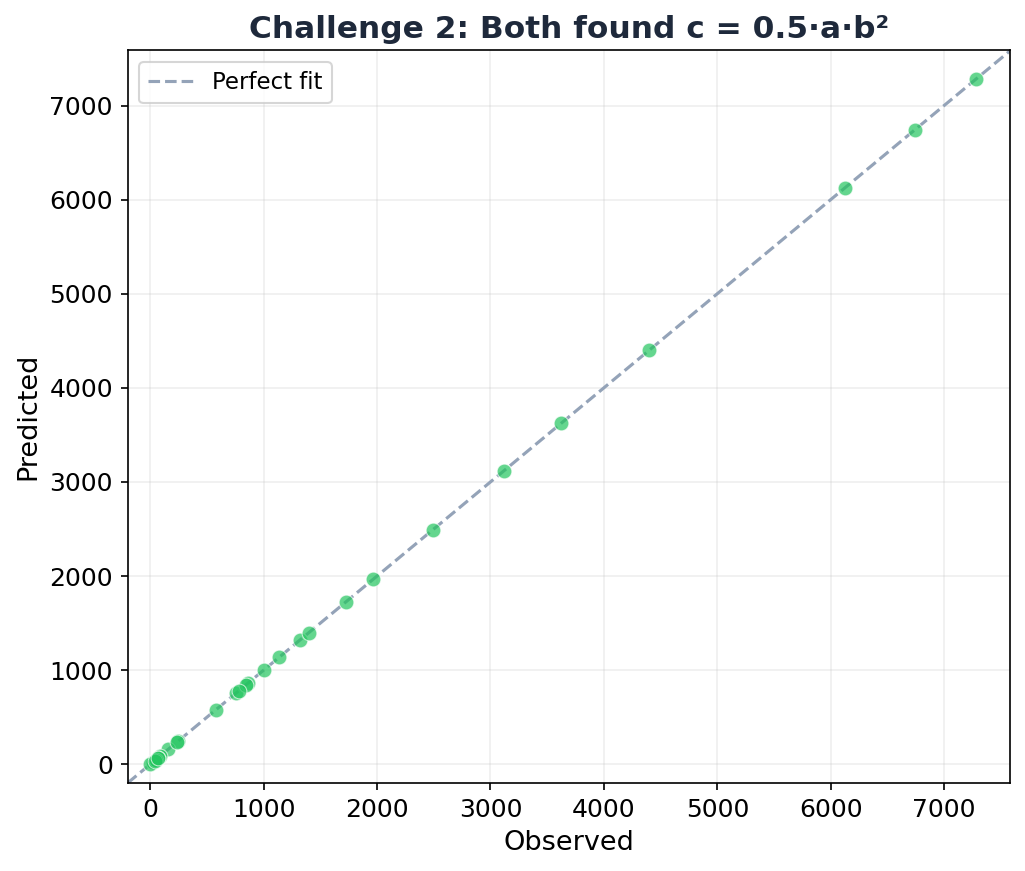

Challenge 2: Find c = f(a, b) from 30 points

This is the kinetic energy equation (E = ½mv²) with the variable names disguised.

ChatGPT's answer:

c = a * b^2 / 2 CorrectTuringBot's answer:

c = 0.5 * a * b * b CorrectBoth nailed it. ChatGPT even verified its answer row by row:

A very strong pattern appears if you try the form c ∝ a · b². Let's test the hypothesis c = a·b² / 2. Row 1: a=23.35, b=12.16 → a·b²/2 = 1725.8. Actual: 1725.78 ✓ [...] This is an exact structural relationship, not a regression fit.

Credit where it's due.

This makes sense: the relationship is a clean polynomial (no transcendental functions), the data had very little noise, and the pattern c ∝ a · b² is something an LLM has likely seen many times in its training data (it's a physics textbook staple).

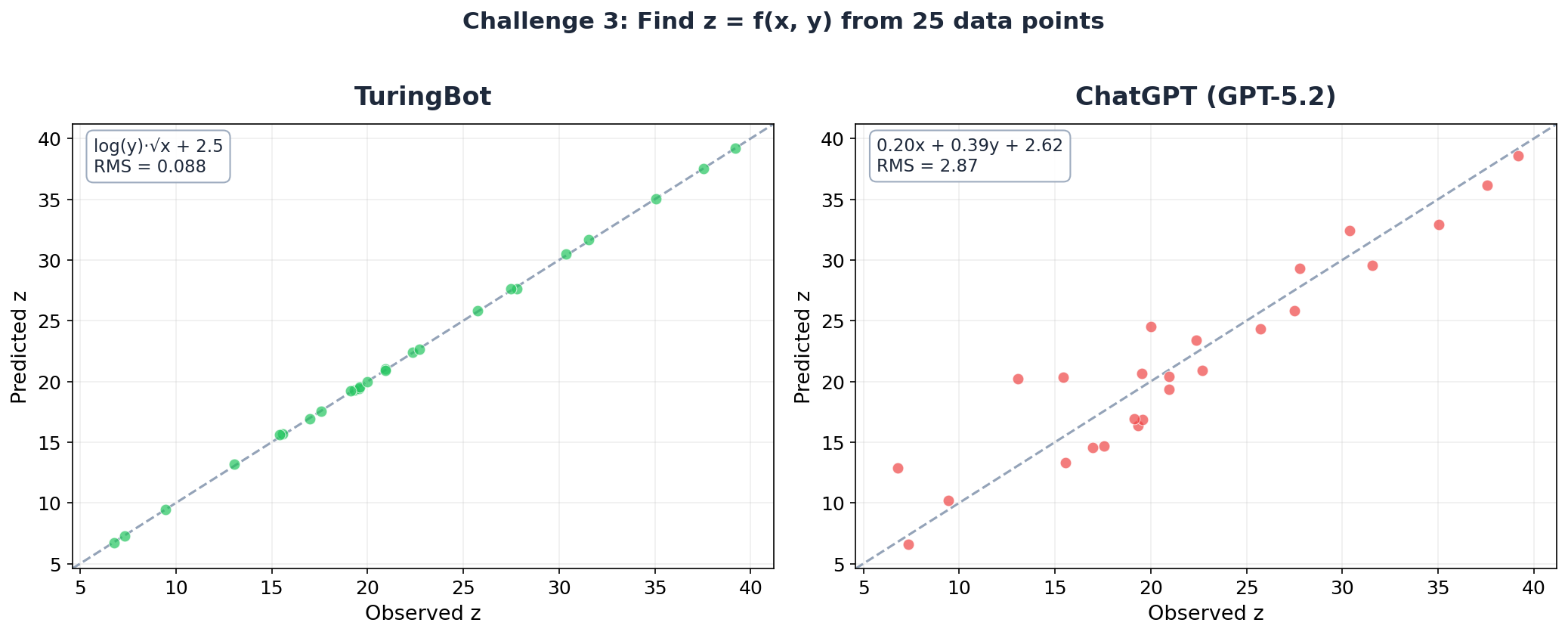

Challenge 3: Find z = f(x, y) from 25 points

Two input variables, a square root, a natural logarithm, and an additive constant. Not exotic, but it requires the model to explore nonlinear function compositions.

ChatGPT's answer:

z = 0.2017*x + 0.3939*y + 2.6188 RMS error: 2.87ChatGPT ran a linear regression and was quite confident about it:

R² ≈ 0.885. This means 88.5% of the variation in z is explained by this very simple linear formula — an excellent indication that the underlying rule relating x,y to z is essentially linear. [...] z ≈ 0.2x + 0.4y + 2.6 is a very accurate rule for this dataset.

But R² = 0.885 means 11.5% of the variance is unexplained, and the model has the wrong functional form entirely. It's a straight line forced through data that follows a logarithmic-square-root curve.

TuringBot's answer:

z = log(y) * sqrt(x) + 2.505 RMS error: 0.088TuringBot found the exact structure with a constant (2.505) within 0.005 of the true value (2.5). The RMS error is 32x smaller than ChatGPT's.

The observed-vs-predicted plot makes the difference visually obvious. TuringBot's predictions fall nearly perfectly on the diagonal. ChatGPT's predictions are scattered, with errors of 3–5 units on data that only ranges from 6 to 39.

Final scorecard

| TuringBot | ChatGPT | |

|---|---|---|

| Challenge 1 y = x · sin(x) | Found exact formula RMS = 0.048 | Wrong structure (fixed-amplitude sine) RMS = 1.81 |

| Challenge 2 c = 0.5 · a · b² | Correct | Correct |

| Challenge 3 z = √x · log(y) + 2.5 | Found exact formula RMS = 0.088 | Wrong structure (linear fit) RMS = 2.87 |

TuringBot found the true formula in all three challenges. ChatGPT found it in one.

Something only Symbolic Regression can do

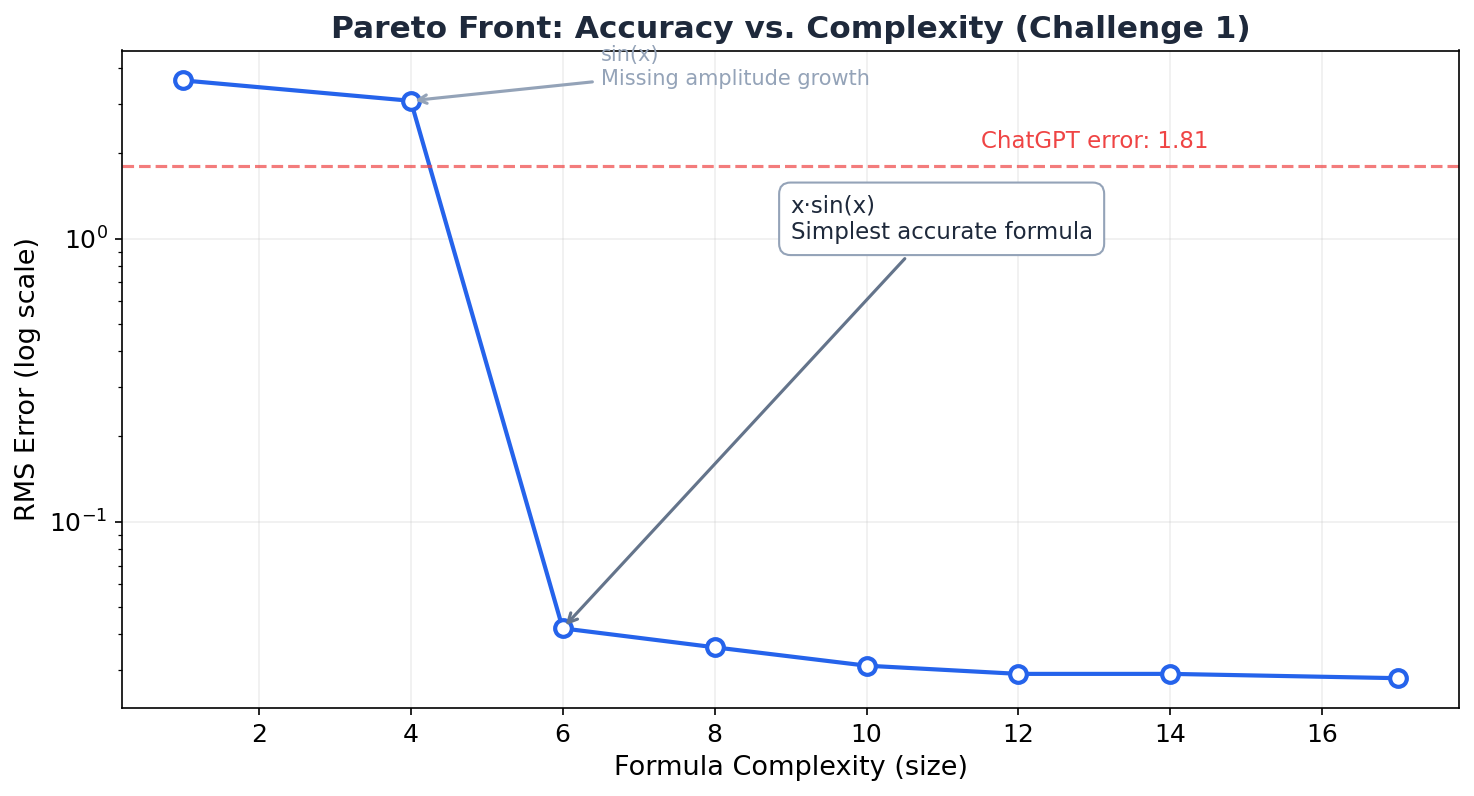

Beyond finding better formulas, TuringBot does something ChatGPT fundamentally cannot: it gives you a Pareto front of solutions — a set of formulas ranked by the trade-off between accuracy and complexity.

For Challenge 1, TuringBot simultaneously found formulas at every complexity level: a constant (just the mean), sin(x) alone (captures oscillation but not the growing amplitude), x · sin(x) (the sweet spot), and progressively more complex variants. You get to choose the right trade-off for your application. ChatGPT gives you one answer and moves on.

Why does this happen?

When you ask ChatGPT to "find a formula," it's not actually searching for one. It's pattern-matching from its training data. Oscillating data? Reach for a sine. Two variables? Try a linear fit. It guesses what formula looks right based on what similar problems looked like in textbooks.

It also produces its answer in one shot. It can't evaluate the formula against the data, measure the error, tweak the structure, and try again. TuringBot does exactly this — it evaluates millions of candidate formulas per minute, combining base functions (sin, log, sqrt, exp, etc.) in novel ways, optimizing both the structure and the constants simultaneously.

There's also the issue of false precision. In Challenge 1, ChatGPT's coefficients (5.0619, 1.0546, −0.4128, −0.1326) are presented with four decimal places, but they're a fit to the wrong functional form. Precise numbers from a wrong model are worse than rough numbers from the right one.

When ChatGPT works (and when it doesn't)

Challenge 2 shows that ChatGPT can succeed when the formula is a well-known pattern (kinetic energy), the relationship is a clean polynomial, and the data is nearly noise-free. In other words, it works when the answer is something it has seen before.

It fails when the formula involves unexpected compositions (x · sin(x) rather than just sin(x)), when nonlinear terms interact (√x · log(y)), or when the answer isn't a textbook formula. Real-world data — noisy sensor readings, experimental measurements, financial time series — almost never follows a textbook formula. That's what Symbolic Regression is for.

Bottom line: if you need to discover mathematical formulas from data, use a tool built for that.

Reproducing these results

Everything in this article can be reproduced. The TuringBot command used for each dataset was:

turingbot /path/to/data.csv \

--search-metric 4 \

--train-test-split 75 \

--threads 2 \

--maximum-formula-complexity 30ChatGPT (GPT-5.2) was given each dataset in a single prompt with the instruction "Find the mathematical formula that describes [target] as a function of [inputs]." No additional hints or context were provided to either tool.

You can also use TuringBot's graphical interface, which lets you load data from a spreadsheet and run the optimization with a single click. Download TuringBot for free and try it on your own data.